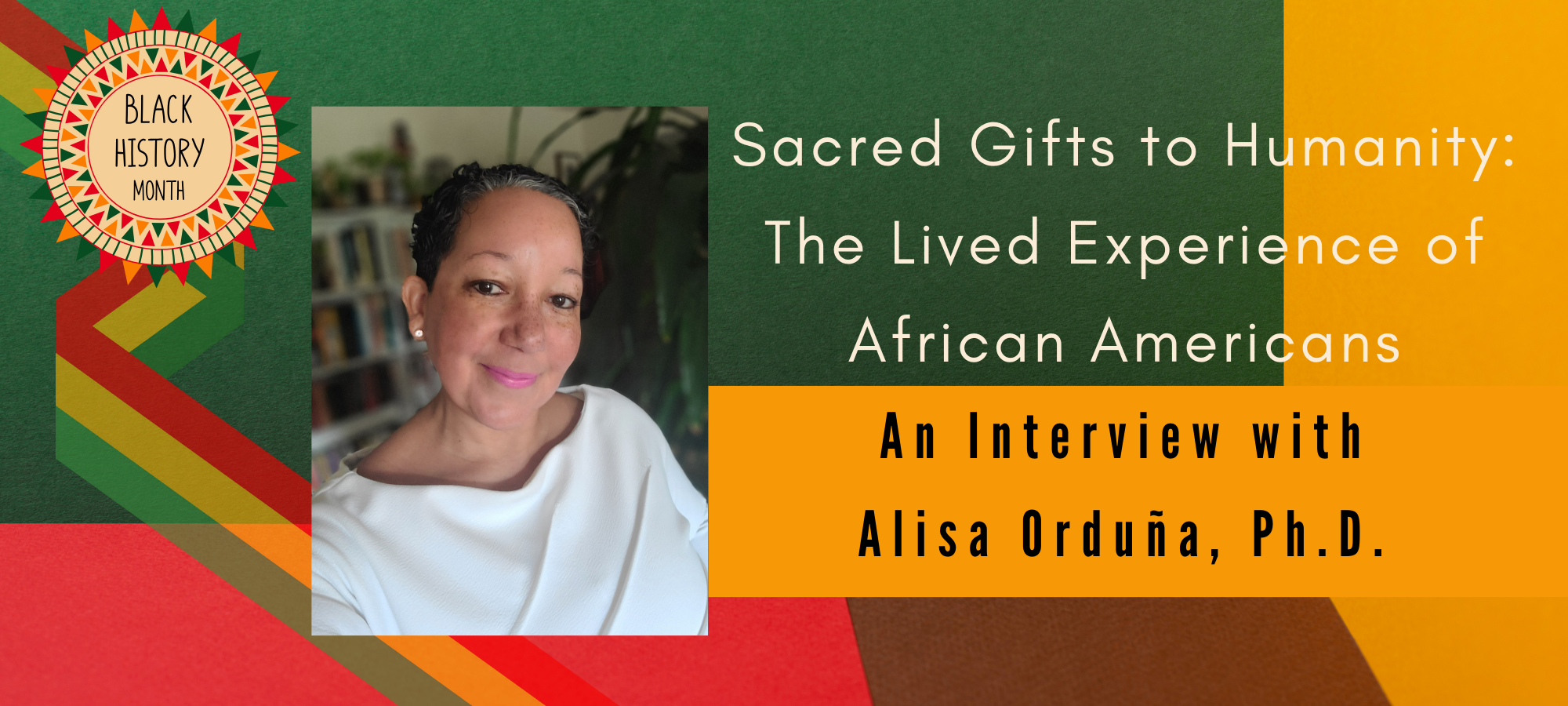

An Interview with Alisa Orduña, Ph.D.

Alisa is a graduate of Pacifica’s specialization in Community, Liberation, Indigenous, and Eco-Psychology. She has been a practitioner, policy analyst, collaborator and thought leader in the urban community development field for the past 25 years. I’m delighted to speak with her.

“I am a collaborator and thought leader in the United States community development field, positioned at the cutting edge of policy formation, community collaboration, racial equity, and system change to work with cities and counties to address the national crisis of homelessness.”

–Alisa D. Orduña, Ph.D.

Angela: Part of what I admire about your career is that, although your scholarship has concerned itself with the profound yet sometimes intangible work of the psyche, you’re actively seeking solutions in the concrete world. There are upward of 200,000 people in California alone, who are homeless. And if my understanding is correct, African Americans make up to 40% of that population. What is happening here, and what practical measures can be taken at the systemic level to address this?

Alisa: First, thank you for your admiration. This work is hard and some days I even wonder to what end I’m working towards. So thank you for seeing it and having an interest. There isn’t one answer, but the common elements that I see are the consistent disbursement of Black communities across the state and the role of anti-Black bias when thinking about who is “deserving” of services. On the one hand, Black communities have been erased through urban renewal projects (e.g., freeways, baseball stadiums, convention centers) and also blight-removal projects, declaring an area blighted and in need of demolition instead of rehabilitation and land, then being sold to private developers for market-rate housing or even golf courses or strip malls. Skid Row’s current status is deeply rooted in this practice. There is also outright land theft—although a free state—there were laws in place in the 1800’s that prevented Black people from owning land. And when white settlers were given land grants, they could easily displace Black communities without consequences. I just read recently that a few Black communities were also flooded and turned into lakes to feed the growing agricultural businesses. These practices prevented acquisition of land that could be transferred across generations to build wealth.

Alisa: First, thank you for your admiration. This work is hard and some days I even wonder to what end I’m working towards. So thank you for seeing it and having an interest. There isn’t one answer, but the common elements that I see are the consistent disbursement of Black communities across the state and the role of anti-Black bias when thinking about who is “deserving” of services. On the one hand, Black communities have been erased through urban renewal projects (e.g., freeways, baseball stadiums, convention centers) and also blight-removal projects, declaring an area blighted and in need of demolition instead of rehabilitation and land, then being sold to private developers for market-rate housing or even golf courses or strip malls. Skid Row’s current status is deeply rooted in this practice. There is also outright land theft—although a free state—there were laws in place in the 1800’s that prevented Black people from owning land. And when white settlers were given land grants, they could easily displace Black communities without consequences. I just read recently that a few Black communities were also flooded and turned into lakes to feed the growing agricultural businesses. These practices prevented acquisition of land that could be transferred across generations to build wealth.

We also cannot underestimate the modern impact of the crack epidemic. At least in Los Angeles, there is proof that this manufactured drug was allowed to enter and flood Black communities, seeding the period of mass incarceration as drug penalty laws became stiffer for users of crack cocaine compared to powder cocaine. This was also the time of the 3 strikes law whereby persons could be sentenced to life for something as small as stealing pizza if it was their third offence. Studies have also shown that when Black people seek help, such as a response to domestic violence or a mental illness crisis, the person who needed assistance (often a Black woman) is charged with a crime and arrested. Through all of these dynamics that undermine the strength of the Black family and community safety net, many Black children end up in foster care with few aging out with the proper skills and social capital for sustainable jobs that enable them to afford our rising housing costs. Finally, employment discrimination continues. I think in an effort to suppress overall wages in the state, a negative narrative pits Black and migrant communities against each other, creating a competition for work that keeps wages low, under the table, and creates conditions of wage theft. All of these factors contribute in one way or another, including negative tolls on health and mental wellbeing.

Tangible solutions include concerted efforts to surface anti-Black bias in our local approaches to policymaking and program design. We not only need more comprehensive trainings and dialogue groups to unlearn our socialization, but we must recruit and promote persons with lived experience of homelessness and being Black while navigating homelessness services to better understand where bias has effected a negative program outcome and rapidly seek to mitigate it. We also need to get ahead of the affordable housing crisis. I personally believe that we need to fund and bring back true public housing. I do not believe that privatization efforts such as low-income housing tax credit projects are sustainable. There is an idea that poverty is temporary, but until we actually provide free healthcare, free or low cost higher education, and diversify jobs so that people of all abilities can thrive, some people may never leave poverty and will need housing subsidies for a lifetime.

We also need more diversity in housing and social service program thresholds. Right now there is such a huge gap between receiving subsidies and market rate, whereby if a person expands the number of hours on their job or receives an increase in their salary, they are penalized by taking all of their subsidies away (such as rental subsidies and healthcare), even if the extra they are making is not enough to afford the market rate cost of these crucial living needs. Finally, cultural and expressive arts are needed as a part of our social services delivery system. This does not just include art therapies, but forms of cultural arts led by cultural brokers in communities as a form of healing, conflict intervention, confidence building, and community bonding. Too many arts organizations struggle, when as we learned locally during the pandemic, it was the arts organizations that quickly pivoted to digital platforms and sent art kits out to members, which saved lives by mitigating negative impacts of social isolation. Arts should not be charity, but funded through public dollars. So in summary: Increase persons with lived experience in all levels of decision making, and increase awareness raising of anti-Black biases and how these impact key nodes within systems that lead to negative outcomes for Black folks, bring back fully funded public housing, and fund cultural arts as part of social services.

Angela: In 2020, you launched your own “community development praxis, Florence Aliese Advancement Network, LLC, a consulting firm serving small to mid-size local cities and counties to address homelessness through the design, research, and evaluation of effective homeless response systems that address historical harm and foster cultures of belonging.” Please tell me more about Florence Aliese’s mission and what lies ahead in your work.

Alisa: Thanks Angela. This is such as great question. I think from my own trauma that I have developed and continue to work through, arising out of my experiencing in the public sector, I recognize a need to bring healing and recognition to staff within public systems, particularly those working on homelessness or other topics that disproportionally impact Black people. So far, I have been fortunate given the attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion methods, however for many this was an emotional response, and I’m not sure how much longer public systems will continue to fund services such as mine (I bring in elements of inter-personal dialogue and other intergroup techniques into meeting facilitation, community engagement with constituent groups, and staff trainings).

While I also have the skill set to focus on traditional homelessness strategies, I realize these do not bring me joy. System-change rooted in advocacy that bring forth tangible changes in outcomes for Black and Indigenous people, really is my jam. Fortunately, I just started teaching a graduate Social Justice seminar at USC within the Price School of Public Policy. So I am hoping to take on a few more courses and also carve out time for research and creative writing to further bring out my ideas around facilitating cultures of belonging out into the world. For instance, in my course, we looked at the phenomenon of homelessness through multiple domains, including race, ethnicity, gender, climate change and mass migration, and disabilities. We examined policies contributing to disproportionate numbers of people experiencing homelessness within these domains and re-imagined new or modified policies to mitigate. From this, I would really like to write a textbook that could maybe change the narrative that homelessness is not just about personal choice, faith-based charity (“the poor will always be with us”), our bad choices, but rather the shadow of our capitalistic society that commodifies housing and community, exploits people and nature, and discards people not “deserving” of being in society. I would also like to earn enough funding to purchase land in Tennessee or Kentucky (the places where both sides of my family experienced and survived the period of slavery) to create a writers retreat center for social justice activists, where they can come and find their voice, as many may not want to pursue a Ph.D. to do so, like I did.

Angela: Thank you so much for speaking with me, Alisa. I learned a lot from your replies and I look forward to seeing your dreams for the future come into being.

Dr. Alisa is a writer and lover of the literary arts, in addition to her work in homelessness policy. She is the author of Oshun’s Calabash, Dancing Across Cuba into the Memory of the Embodied African Soul & Finding Home and Unearthing the Feminine. She is a contributing author to Seeing in the Dark: Wisdom Works by Black Women in Depth-Psychology.

Alisa is a Los Angeles native and enjoys spending time reading, in nature, or being present for her nephews.

Angela Borda is a writer for Pacifica Graduate Institute, as well as the editor of the Santa Barbara Literary Journal. Her work has been published in Food & Home, Peregrine, Hurricanes & Swan Songs, Delirium Corridor, Still Arts Quarterly, Danse Macabre, and is forthcoming in The Tertiary Lodger and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 5.