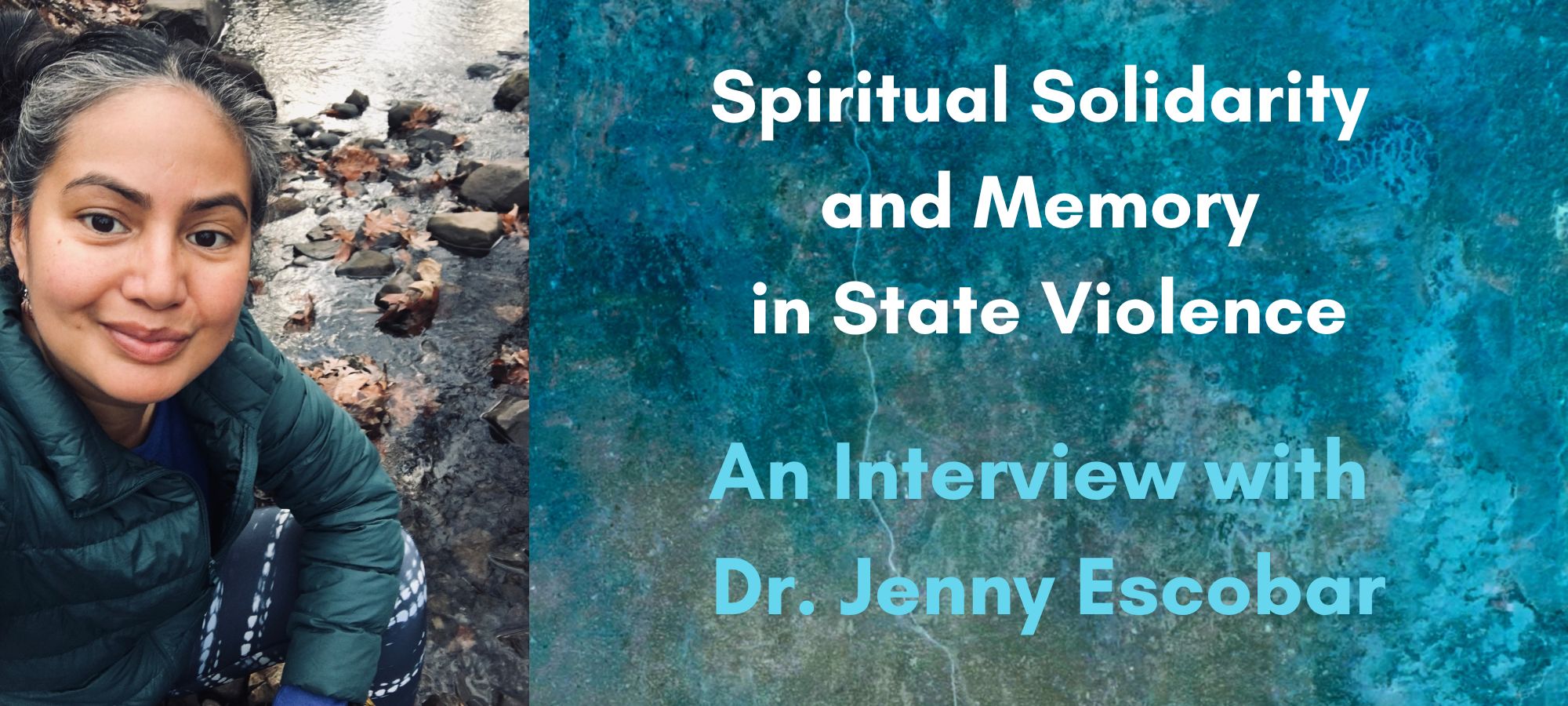

Pacifica is pleased to welcome Dr. Jenny Escobar to the position of Core Faculty in the M.A./Ph.D. Program in Depth Psychology with Specialization in Community, Liberation, Indigenous, and Eco-Psychologies. Dr. Escobar began teaching this fall, and I’m delighted to find out more about her work.

Angela: You come to Pacifica with a B. A. in Forensic Psychology and a Ph.D. in Social Psychology with an emphasis in Latin American/Latina(o) Studies. Tell us a little more about your academic journey and research. What drives or inspires you to combine psychology with Latina(o) studies?

Jenny: I have found psychology to be the driving force for understanding social justice initiatives. As an undergraduate, I majored in forensic psychology because I was interested in understanding why we do what we do, and forensic psychology is about understanding people who commit what we call crimes and the psychosis for why people do “deviant” behavior. Within that framework I was able to be critical of the way psychology describes our behavior without taking into account the social structures around us like homophobia, racism, poverty, and the systems of oppression that contribute to people’s behavior. It’s this notion of complicating our understanding of the individual within systems and histories of violence that led to my Ph.D. topic.

We are being impacted by systems of violence and oppression on a daily basis. I was experiencing that myself as an undocumented immigrant. I also saw the resilience and strength my family brought to the table to navigate that. As a result, I wanted to investigate the things that keep us strong, connected, and grounded in a context that dehumanizes. I returned to Colombia, where I was born, and went on a journey of understanding survivors of state violence’s trajectory through violence. Survivors have and continue to experience violence at the hands of the state, military, police, and paramilitary groups funded by the state. What I ended up witnessing was the way they use memory practices to commemorate loss and a way to initiate action for justice, truth, and reparations.

After finishing my doctorate, I focused my work in the United States working with families of color who were experiencing gentrification in San Francisco, and young people in California using restorative justice practices to name their experiences of exclusion and violence from the school-to-prison pipeline. I saw the connection between young people here in the United States and the violence in Colombia as a similar grief and lack of safety they felt from systemic violence, and the loneliness of not being believed by the larger community. Part of the collective healing work we did was to create a space for their truth and social justice demands to be heard and carried out.

One of my biggest motivations for coming back into academia was to explore our unlimited imaginative power to dream and create something different than systems of violence. I found that we as humans can be limited in the way we imagine our futures to be outside of these systems of oppression. Connecting with spirit, the land, and the nonhuman world can provide us a larger sense of belonging and a broader way to imagine what can be possible when we let go of what we think we know. I’m drawn to Pacifica for the connection between liberation psychology, spirit, and the indigenous relational cosmovisions with the land. All for the sake of reimagining healing from a land-based perspective and not just from a place of trauma.

Angela: We’re delighted to have you here in the CLIE program. What draws you to Pacifica and CLIE in particular?

Jenny: This program is unique within psychology; it’s a decolonizing practice and theory, a place where we can practice decolonizing psychology. It feels like an academic and intellectual community that is moving through and past conversations about the role of psychology in social justice initiatives. Psychology is meant to be about the liberation of all people; that is a given understanding in this program, and we’re asking not if psychology can be at the heart of justice but rather how it can be. It’s as if a home was built here for me. Some questions that guide me right now are how can we build a relationship with the rivers and the waters around us in a way that is reciprocal? And as we’re caring for the land, are we learning what is possible for us in our healing and justice practices? If we were to pay attention to how the land heals, regenerates, and addresses injustices, what would be the lessons we can take? In the article I wrote about Spiritual Solidarity, I also highlighted the role of ancestors, those who are no longer here, and their power to provide us with a roadmap of how to navigate ongoing social violence. Breaking the dichotomy between the human and non-human is how I believe we’re going to find the visions and roadmaps to healing and justice practices that will help us get out of circular cycles of violence and oppression.

Angela: I understand that your research focuses on collective social justice strategies led by survivors of state violence who transform trauma into healing and state violence into justice. Assuming that you specialize in South America, my frame of reference for this goes back to the 1980s when the Disappeared in Argentina were a common point of news discussion. My general sense of South American political history is that it is often fraught with extraordinary violence. How do you describe this in psychological terms? Is the government some kind of archetype? Is this some larger projection of violence learned in the family or is it something else?

Jenny: From a liberation psychology stance, in order to understand the impact of violence, whether for a survivor or the person committing the violence, we have to take into account the traumatogenic structures that led to the violence in the first place. Ignacio Martin Baro, a liberation psychologist who termed traumatogenic structures contended that focusing on the structures that cause the trauma leads us to look beyond the individual actions and into the root of where the violence and trauma is emerging. By focusing on the traumatogenic structures, the onus is on changing these structures instead of pathologizing the individual. In other words, liberation psychology ask us to look at how an individual is impacted by the social structures that surround them.

Angela: Given the amount of people missing or blatantly jailed or murdered in South America, and the ongoing or cyclical nature of it, how can we seek healing for those directly affected? Your work embraces spiritual solidarity and memory as social strategies. What does that look like?

Jenny: We come together with other people with similar experiences through stories, art, and social justice organizing. Sharing not only the stories about the details of the violence, but stories that humanize them again. I found myself at different gatherings with survivors, sharing over food, conversations about what they like to do, what their children are doing, illuminating who they are as people outside of their experiences of violence. I’m not the one to say that was healing for them, but it felt to me like a nourishing practice, they were able to find the energy and strength to continue to fight for justice and demand that something be done about the violence that was committed. The connection between social justice work and healing is palpable. I didn’t see people saying it was enough to talk about what happened, it had to be connected to their social justice demands. In the United States too, people of color don’t want to just talk among themselves about what is wrong, they want change and they have clear ideas of how they want this to happen. Healing comes through the connection with others and the clarity of having justice demands heard and accounted.

Angela: What courses will you be teaching at Pacifica, and how do they relate to you research? What are you most looking forward to teaching?

Jenny: In the fall, I am co-teaching Participatory Research. In the winter and spring, I am teaching Psychologies of Liberation, Restorative Justice and Foundations for Research. These courses connect directly to my research in that we will be exploring a decolonial stance and practice in partnering with communities for the sake of co-creating research and epistemologies that lead us into liberation and healing.

Angela: Thank you so much for speaking with me, and I look forward to seeing your teaching career at Pacifica unfold.

Dr. Jenny Escobar is a member of the Core Faculty at Pacifica Graduate Institute. Her research interests stem from personal experiences as a first-generation immigrant from Colombia. Dr. Escobar’s transdisciplinary research focuses on collective social justice strategies led by survivors of state violence who transform trauma into healing and state violence into justice. More specifically she focuses on the use of memory practices and transnational spiritual relationships of solidarity. As a transformative justice practitioner, she captures the strength and imaginative capacity of survivors by facilitating spaces for healing and for justice demands to emerge. Currently she is working on exploring the healing and justice teachings that nature has for us by examining the relationship between Indigenous, Afro-Colombian and campesinos and their connection to the land. Her work has appeared in the American Journal of Community Psychology and she is currently working on a book titled Love as Remembrance: State Violence and the Movement for Memory in Columbia (upcoming book proposal for Oxford University Press). Overall, Dr. Escobar is committed to bringing a decolonial, liberation psychology approach by embodying a research ethos based on reciprocal relationships, community accountability, and a psychology for and with survivors of state violence.

Angela Borda is a writer for Pacifica Graduate Institute, as well as the editor of the Santa Barbara Literary Journal. Her work has been published in Food & Home, Peregrine, Hurricanes & Swan Songs, Delirium Corridor, Still Arts Quarterly, Danse Macabre, and is forthcoming in The Tertiary Lodger and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 5.