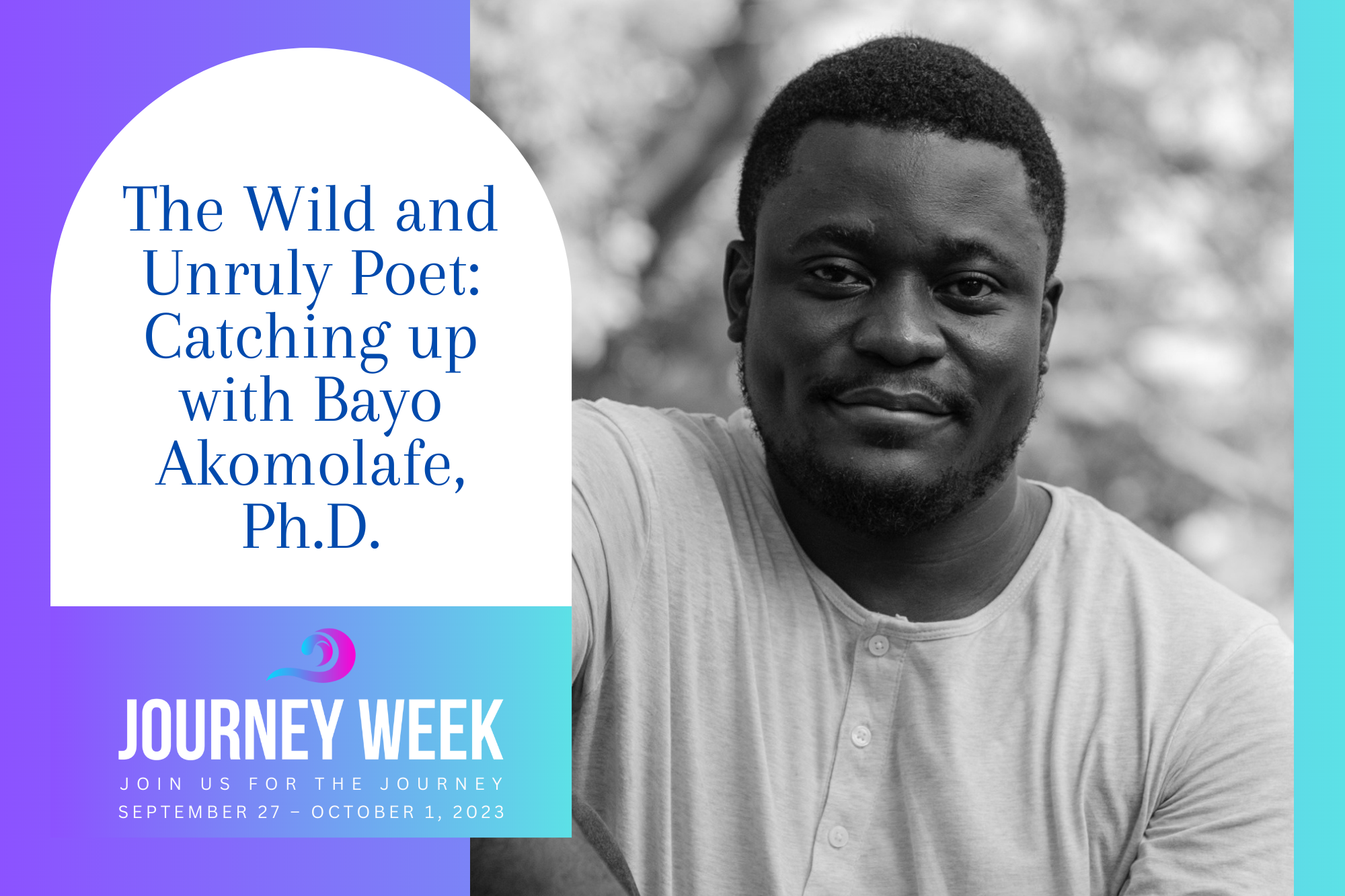

As part of Pacifica’s Journeys of the Soul Conference, an immersive weekend of learning and connecting at Pacifica Graduate Institute to be held September 29 – October 1, Bayo Akomolafe, Ph.D., an adjunct lecturer at Pacifica, a poet and the Executive Director and for The Emergence Network, will offer a special long-distance welcome and introduction to the conference. I’m delighted to speak with him about his work and history with Pacifica.

As part of Pacifica’s Journeys of the Soul Conference, an immersive weekend of learning and connecting at Pacifica Graduate Institute to be held September 29 – October 1, Bayo Akomolafe, Ph.D., an adjunct lecturer at Pacifica, a poet and the Executive Director and for The Emergence Network, will offer a special long-distance welcome and introduction to the conference. I’m delighted to speak with him about his work and history with Pacifica.

Angela: You’ve said of Pacifica, “Good questions live in Pacifica. Good, wild, fantastic questions. They live in the eyes, the faces, the smiles, the rituals, the humility, and the teeming everydays of this fine institution. To learn, teach, and mentor here, no matter your specification, is to become part of a collective inquiry for unspoken depths, for discarded memories, for lingering ancestries, for new political imaginaries, for exquisitely new ways of saying and doing things.” We are fortunate to have you here as an adjunct lecturer in our CLIE (Community, Liberation, Indigenous, and Eco-Psychologies) program. What has it been like to teach here and how did you find Pacifica?

Bayo: Pacifica found me, actually. Professor Susan James of the CLIE program asked me to teach. I did my Ph.D. in Nigeria twelve years ago in clinical psychology, focusing on indigenous ways of healings and diagnostic models and especially how Yoruban shamans saw and understood and treated mental illness. I was attracted by CLIE’s emphasis on postcolonial liberation, indigenous ways of thinking, the subversion of “enlightenment” thinking. The invitation to think differently gives room enough for me to spaciously convene new concepts. So I consider myself a public intellectual, and Pacifica and CLIE stand as a beautiful oasis, a watering ground for bold and courageous thinking.

Angela: You are an accomplished author and poet, having written These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home and We Will Tell our Own Story: The Lions of Africa Speak. How do you conceive of the poet or the writer’s role in our current world? And are you working on anything currently?

Angela: You are an accomplished author and poet, having written These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home and We Will Tell our Own Story: The Lions of Africa Speak. How do you conceive of the poet or the writer’s role in our current world? And are you working on anything currently?

Bayo: I’m writing a couple of books, A Pedagogy of the Cracks is one, and An Ocean of Milk is the other; I’m writing them concurrently. The poet’s vocation is to speak wildly and madly and to offend, to break and distort the sensorial prisons that keep us tethered to ways of familiarizing the world. The poet is not even a human, the poet is a moment, the pen, the writer, the materials, and the instigation that creates moments of upset. I probably wouldn’t consider myself some kind of original poet. I think the gift of culture, place, and experience, and the enlistments of beautiful pedagogies, indigenous ideas, feminist materials that assert our imbrications with the world, these are the milk I feed on. That is the food that nourishes me. The things I would attribute to myself, whether it’s voice, skill, or gift, is a lot more diffracted than we think.

Angela: You are the Executive Director and Chief Curator for The Emergence Network, whose website begins with the question “What if the way we respond to the crisis is part of the crisis?” What is the work of the network and what do you find most rich and valuable in it? How does it relate to “postactivism,” a term you use often in your work?

Bayo: It’s a work of subterfuge of some kind. It’s subterranean, an invitation to seed a different kind of politics that might look more like a network and small intense spaces rather than some grand scheme to save the planet. It’s a thinking and explorative inquiry into postactivism. A fugitive, underground network of carnivals and festivals that see our times as powerful occasion for new kinds of departures, experiments, and gestures.

Postactivism is my way of thinking about the ways we’re summoned by our critique of problems before us. That is to say, if you see a problem, let’s say climate chaos, it is impossible to think of this problem gaining intelligibility without noticing how we are entangled in that phenomena. We’re not just naming a world outside of us; the problems we articulate will articulate us in return. Critique is a double agent: it calls out systems of oppression, but it reinforces those systems as well. It uses the resources of that moral space to address its issues. So in some sense, the way we think about the problem is the problem. Change is not entirely left to us. It’s not for us to change the world; there’s something hubristic about saying that. To think about the world as just this theatrical space where humans act out our lives, and the rest of the world is just a background for that…there’s something about that that feels very troubling.

Angela: One of the concepts mentioned in your work is “transraciality.” Can you speak a little about this and how it relates to your world view or mission?

Bayo: Transraciality tries to think of racial identity through processes or rather through the pre-individual, another concept associated with the philosopher Gilbert Simondon. The pre-indiviual is not the stable self with an identity, instead identity is co-formulated within a network of radical becoming. I’m trying to see bodies in motion, skin in motion, edges and boundaries constantly travelling, thresholds scandalously moving from place to place. You are not just the person apparent to me; you’re also the textures in the room, the architecture, the field in movement. In literal terms, your boundaries are ecologically exposed to the world around you and you’re being made in this moment. It’s very modern to think about people as fitting within predetermined labels and signs, to categorize them under generic headings. This is what white modernity does well by separation. So when we see bodies as fluid and intense and not these dispassionate, isolated things, then identity becomes unwieldy and unruly. It’s neither good nor bad, it depends on the space within which these matters are conceived and met. It is troubling in a sense to the civilizing ethic of modernity to think of them as unwieldy and so sensuous they can’t stay still. There’s something decolonial and liberating about this.

As such, transraciality is the view of how bodies come to become racialized through a refusal to situate bodies and identities as faits accompli. The analysis here is that bodies—liberated from the burden of inheritance—are horizontal practices: manufactured, not born. Black bodies are not merely born; they are stitched together within sociomaterial practices of shared becomings, through language, through material exclusions, through markings, through technology. Race is not a stable thing that is merely inherited.

Angela: Thank you so much for speaking with me. Your words and ideas are very needed now, and I look forward to reading your two new books and hearing you speak at Journey Week.

To hear Bayo Akomolafe’s speak and connect with other nationally recognized leaders, scholars, and authors, please join us for Journeys of the Soul Conference, an immersive weekend of learning and connecting at Pacifica Graduate Institute to be held September 29, 2023-October 1, 2023.

Angela Borda is a writer for Pacifica Graduate Institute, as well as the editor of the Santa Barbara Literary Journal. Her work has been published in Food & Home, Peregrine, Hurricanes & Swan Songs, Delirium Corridor, Still Arts Quarterly, Danse Macabre, and is forthcoming in The Tertiary Lodger and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 5.

Bayo Akomolafe (Ph.D.), rooted with the Yoruba people in a more-than-human world, is a widely celebrated international speaker, posthumanist thinker, poet, teacher, public intellectual, essayist, and author of two books, These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home (North Atlantic Books) and We Will Tell our Own Story: The Lions of Africa Speak.