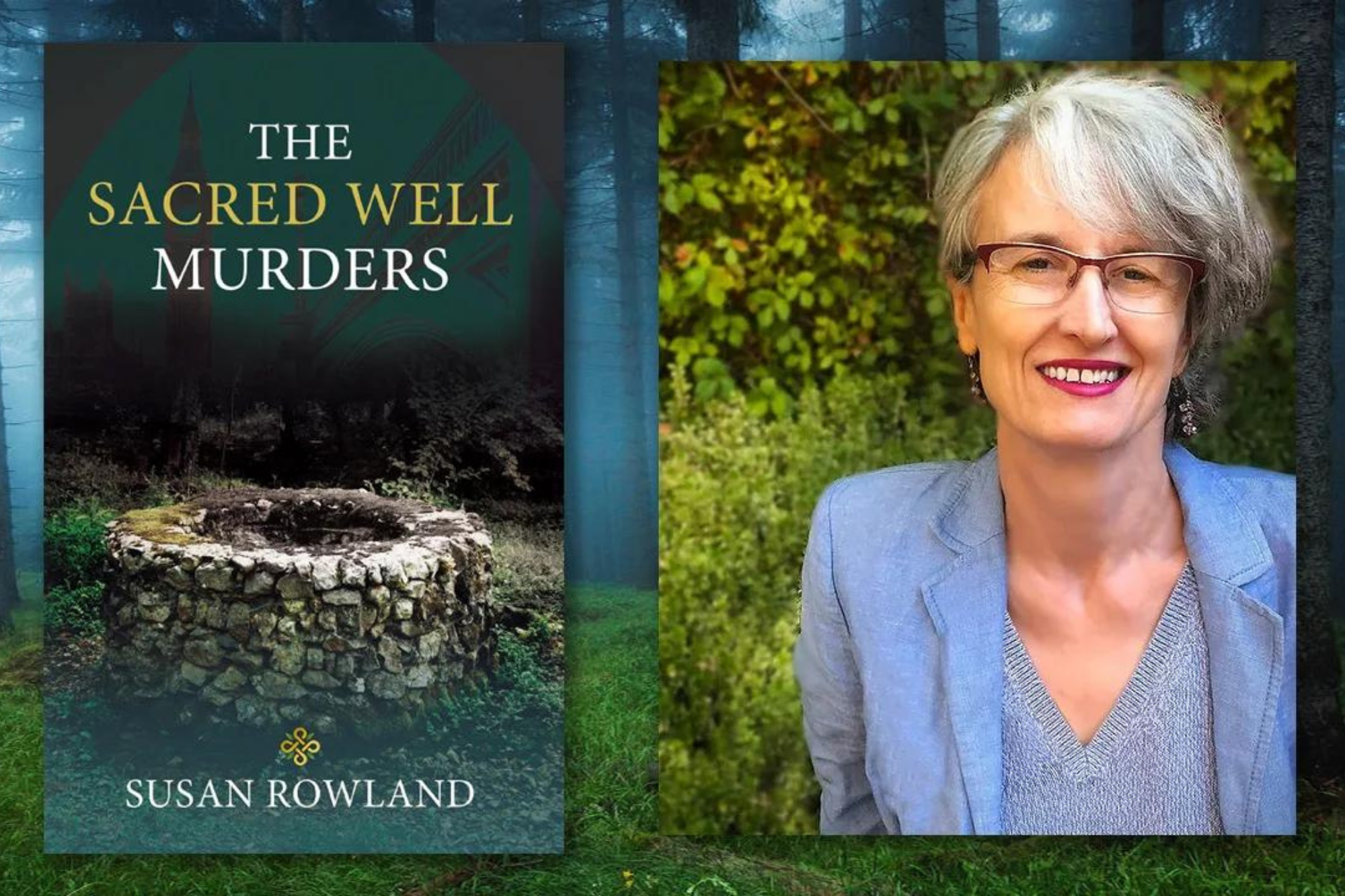

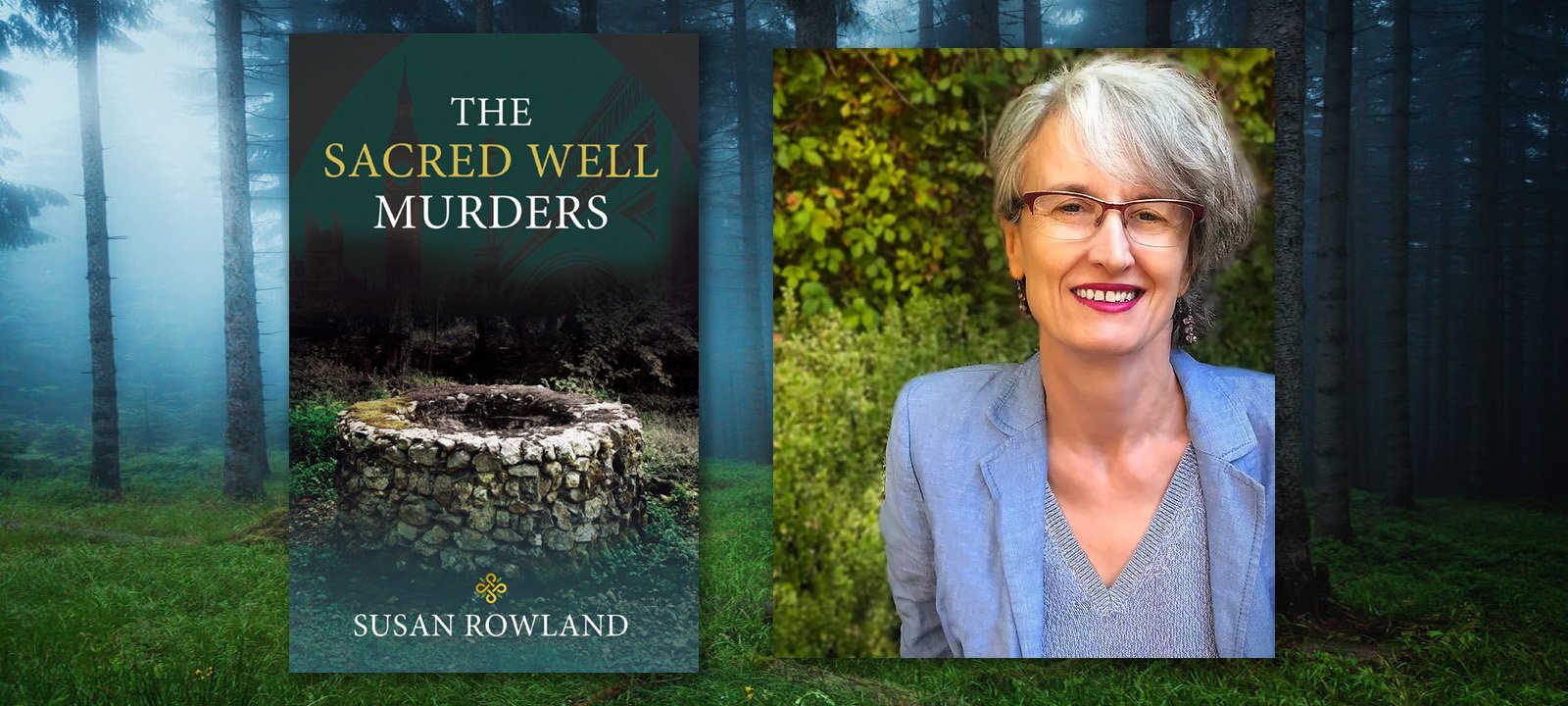

Susan Rowland, core faculty at Pacifica Graduate Institute, and author of The Sleuth and the Goddess in Women’s Detective Fiction, among other works of academic writing and fiction, has just had a new book published by Chiron Publications, The Sacred Well Murders. “A simple job turns deadly when Mary Wandwalker, novice detective, is hired to chaperone a young American, Rhiannon, to the Oxford University Summer School on the ancient Celts. Worried by a rhetoric of blood sacrifice, Mary and her operatives, Caroline, and Anna, attend a sacrifice at a sacred well. They discover that those who fail to individuate their gods become possessed by them.” I was delighted to speak with Susan about her new novel, which is available on amazon here.

.png?width=233&name=Untitled%20design%20(31).png)

Angela: Your novel stands alone as a mystery novel, but takes on deeper dimensions with themes of climate change, racism, and PTSD. Of your novel, you’ve said, “It looks at people traumatized by war or family breakdown in the context of acute anxieties about the climate emergency. The Sacred Well Murders argues that there is a psychic and social dimension of ecological crisis hitherto neglected by the powers that be.” I know that scholars at Pacifica are, rightly, very engaged with matters of ecological crisis and also our human psyche extending to the natural world around us. Please talk more about the “psychic and social dimensions” that you referred to, and how did you weave that into your novel?

Susan: Thank you for asking such an important question, Angela. The Sacred Well Murders is a tiny contribution to a major question of our age: What are the obstacles to addressing the climate emergency? Why are we so slow to change when change is vital for our future? More consciously debated in the twenty-first century is the question of terrorism. I wanted to look at why people—ostensibly good people—might be drawn into public acts of violence for a cause. It seemed to me that the climate emergency is adding a layer of fear onto an already overwhelming overload of trauma in this century. So, I have an instigator who is a veteran suffering from unbearable PTSD. He desperately needs help from the deep psyche of archetypes. Unfortunately, his trauma means he is possessed by gods rather than being able to individuate them. A similar fate occurs to some members of the Morrigan family who have endured incredible losses and drug addiction. My heroes, my three women detectives, alone can prevent the worst from happening.

A significant dimension of the story is the value of indigenous perspectives on humans in relation to nature. For these are societies embedded in mutual sustaining relationships with the land they live with rather than “on.” Every one of us has indigenous heritage, but for people like me, it is 2,000 years away, when the tribal Celts dominated all of Europe. Celtic societies held water sources to be sacred; they made offerings to them. The propaganda of their enemies, the Romans, alleged that the Celts practiced human sacrifice—now regarded by scholars as not true. However, when modern seekers for ancient truths become possessed by archetypes, such a reputation can be very dangerous.

“Before the river was left to gulp for breath in sacred wells. In those untamed days the river we call the Thames was holy.”

–Sacred Well Murders

Angela: The story centers around fictional “Reborn Celts,” whom are intent on bringing back the old ways, via “waking the water” at three wells. What do wells symbolize to you, and how did you settle on them as the conduit in your novel between nature’s power and the world of humans? What is the significance of water here? I have no doubt you considered this through the lens of both depth psychology and Celtic tradition.

.png?width=233&name=Untitled%20design%20(34).png) Susan: Well done for spotting the dual symbolism. In fact, The Sacred Well Murders is one of a series of Mary Wandwalker mysteries focused on the alchemical elements, here water. I have nearly completed manuscripts on earth and fire. As noted above, the Celts held freshwater sources to be sacred and portals to the Otherworld. In fact, the earliest version of the Holy Grail story is “the well maidens of Logres,” in which maidens tended the holy wells between the worlds. They would offer travelers the divine water in a cup. Until one day when a king rode by with his knights and, instead of accepting the water as a gift, raped the well maiden. When the knights did the same at the remaining holy wells, the divine springs dried up and the land became waste. What an important story for the 21st century as we see the repression of the feminine take monstrous shape in the wasteland of the climate emergency, traumatized psyches, and remorseless acquisitive capitalism!

Susan: Well done for spotting the dual symbolism. In fact, The Sacred Well Murders is one of a series of Mary Wandwalker mysteries focused on the alchemical elements, here water. I have nearly completed manuscripts on earth and fire. As noted above, the Celts held freshwater sources to be sacred and portals to the Otherworld. In fact, the earliest version of the Holy Grail story is “the well maidens of Logres,” in which maidens tended the holy wells between the worlds. They would offer travelers the divine water in a cup. Until one day when a king rode by with his knights and, instead of accepting the water as a gift, raped the well maiden. When the knights did the same at the remaining holy wells, the divine springs dried up and the land became waste. What an important story for the 21st century as we see the repression of the feminine take monstrous shape in the wasteland of the climate emergency, traumatized psyches, and remorseless acquisitive capitalism!

And yet we can still find the original Celtic sacred wells. Sometimes they are untouched natural springs where folk tie strips of cloth to the bushes to signify requests for healing. More often, the sacred springs continued to be venerated during the Roman occupation and into Christianity, which often sited churches over or near them. In medieval times the sacred spring became a well, with a stone shaft and the many place names holywell, ladywell, saltwell, records their legacy. In London, some sacred wells can still be seen, such as the Clerk’s Well in Clerkenwell that comes into the novel. Equally important were rivers as divine portals. We know the Celts made offerings in lakes and rivers as large as the river Thames. The Arthurian legend of a sword coming from, and returning to a lady in a lake, is surely a Celtic survival. In my book, as well as sacred wells receiving misguided gristly tribute, there is also a nefarious scheme to revive one of the lost rivers of London. This too has historical basis: London has a network of underground rivers once part of a Celtic divine landscape.

“Many decades ago, the Holywell women decided to reframe their mission. Formally training as therapists meant they could enter the National Health Service. The only snag was, they were required to give up using their magic on patients.”

–Sacred Well Murders

Angela: Your novel has many delightful “Easter Eggs” for anyone interested in depth psychology. The investigative agency of the main character is named Depth Enquiry Agency, to begin with. And the start of the story is Holywell, a school run by witches, who in the modern day have traded spells for psychology, and work as therapists for traumatized girls. Did you mean to draw a parallel between witches (those who parlay with the elements, nature, the divine) and psychologists? I think anyone who has had a good therapist will equate what they do to magic. It seems an interesting archetype for you to choose in this case.

.png?width=233&name=Untitled%20design%20(32).png) Susan: Yes, I did mean to draw a parallel between nature-oriented witchcraft and depth psychotherapy. My fictional ‘Holywell’ knowingly connects the deep indigenous past with magical traditions that keep some Celtic practices and belief. These are then brought into the modern era by training in depth psychology. In the story, the Holywell witches are the “good guys” because they individuate their goddess rather than become possessed by divine fury. There is a character, Janet, who is an elderly witch who nevertheless feels the need for external help from the skeptical Mary Wandwalker when one of her charges, a traumatized young woman, gets the wrong idea about magic and starts using human blood. The novel has a lot of comedy and I just had to have the line: There was a choking sound from one corner of the table. Janet remained grim. “Time to get real, Sarah. No more human sacrifices, got it!”

Susan: Yes, I did mean to draw a parallel between nature-oriented witchcraft and depth psychotherapy. My fictional ‘Holywell’ knowingly connects the deep indigenous past with magical traditions that keep some Celtic practices and belief. These are then brought into the modern era by training in depth psychology. In the story, the Holywell witches are the “good guys” because they individuate their goddess rather than become possessed by divine fury. There is a character, Janet, who is an elderly witch who nevertheless feels the need for external help from the skeptical Mary Wandwalker when one of her charges, a traumatized young woman, gets the wrong idea about magic and starts using human blood. The novel has a lot of comedy and I just had to have the line: There was a choking sound from one corner of the table. Janet remained grim. “Time to get real, Sarah. No more human sacrifices, got it!”

Angela: Racism is also a topic that you touch on in this book, as the “Reborn Celts” (fictional, keep in mind) are a group that are said to have racist tendencies, as well as a misguided notion that blood sacrifice is needed to bring the water to life. You have several characters of color in the book who may be put in peril by this. But you also give us the dilemma of making the main antagonist a war veteran suffering from PTSD, something that most of us have great empathy for. I think this may be leading us to the conclusion that “Hurt people hurt other people.” What was your intention and perspective on this as you wrote the book?

Susan: Yes, I wanted this story to explore how good people might get drawn into something terrible through their own wounds becoming intolerable. It seemed to me that we are in a new era of even more toxic racism and that there is a real danger of the longing for indigenous cultures getting mixed up with racist fantasies. In fact, with race not a meaningful factor in BCE Europe, the actual Celts were not white in the modern sense, as I show in the book. However, this new fictional group, the Reborn Celts, do attract some of the most noxious elements of our age.

Moreover, a character I’m very fond of and who appears in all my novels is known only as Mr. Jeffreys because he is so high up in government circles that no one knows his first name. He is an Englishman of African descent and Mary’s regular verbal sparring partner. My favorite glimpse of him in The Sacred Well Murders is when the tough guy rescue team he puts together reject him on the grounds of his age, and he turns up among Mary’s unofficial rescuers looking like a bluebottle in blue lycra. Mr. Jeffreys is part of an attempt to write the world we want as well as point to fractures in the world we have.

Angela: As part of Pacifica Retreat’s series Redreaming a World in Crisis, you are giving a talk on March 20 titled “Writing the Flawed Woman as Hero in an Age of Crisis.” In your novel, is Mary Wandwalker a flawed woman as hero? And what may people look forward to in your talk?

Susan: For years and years, I have been working on the idea of an alternative to the so-called “hero myth,” which is a derivation from a huge number of myths constructed by Joseph Campbell. To Campbell, this myth points to a route to heroism for men and not for women. While several scholars have put together a hero story for women, I suggest both these approaches are too literal and too binary. And yet, I must admit to dreaming my flawed women heroes from another mythic interpretation by a man, Robert Graves’s idea of the triple goddess as maiden, mother, and crone.

.png?width=233&name=Untitled%20design%20(35).png) My defense of the triple goddess as a trio of flawed women heroes (who are also in some sense one being), is that Celtic goddesses frequently appear as maidens and crones: the pairing arises again and again. My trio are marginalized women coming into their power—or at least voice—from the margins.

My defense of the triple goddess as a trio of flawed women heroes (who are also in some sense one being), is that Celtic goddesses frequently appear as maidens and crones: the pairing arises again and again. My trio are marginalized women coming into their power—or at least voice—from the margins.

Mary Wandwalker is a crone because aged 60 she was fired from her job and had to face the fact that she had no family and no money. She then meets Caroline, the middle-aged widow of Mary’s long-lost son. Not literally a mother, Caroline has nurturing qualities despite of, and because of, suffering from chronic clinical depression. Caroline is also the partner of her husband’s former girlfriend, a much younger woman that her husband helped to rescue out of trafficking. For me, the trafficked woman is an icon of our times. Anna is a virgin, not because she has never had sex, but because she has never had love. Native to a very dark underworld, Anna has great vulnerabilities and extraordinary powers.

Together these three women from the margins begin to understand the archetypal energies they can command when working together. They are ultimately a feminine flawed hero where the flaws are necessary to figuring a net of compassion and multiple ways of knowing. I will be exploring the implication of all these ideas in the talk I am giving.

Angela: For many years you were the co-chair and chair of Engaged Humanities & the Creative Life at Pacifica, now core faculty in the renamed M.A. In Depth Psychology and Creativity with Emphasis in the Arts and Humanities program. The purpose of the program, or one of its main purposes, is to “Cultivate students’ aesthetic sensibility and creative powers through deep engagement with the creative psyche.” And many people finish the M.A. program and go on to turn out magnificent works of literature, film, art, etc. You’ve certainly shown yourself to be both a teacher of these ideas as well as a creative generator in your own right. What is the relationship for you between being an author and being a teacher of this program, especially as it relates to depth psychology?

Susan: One of the extraordinary things about teaching at Pacific is the sacred well of creativity that is manifested in the classes. Teaching on the Engaged Humanities program, now renamed Depth Psychology & Creativity, I was able to explore the partnership between psychic practices and what can be manifested in making art. I was in-spirited or inspired by students who were discovering enormous depths in their creativity because they were learning to integrate it with depth psychology. Synchronicities abound in the way psychic patterns emerge within and between the students.

The Sacred Well Murders owes a great deal to Pacifica’s dedication to the psyche as innately creative, and to the humanities MA, in particular. My character Mary Wandwalker would be skeptical of a lot of what we do. However, my character Caroline would embrace the MA with joy as it helps her to cope better with her depression, while Anna would make enigmatic and beautiful sculptures while speaking to no one!

Angela: That you so much for writing The Sacred Well Murders and sharing your thoughts here.

Susan Rowland, PhD, is Chair of the Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life Program at Pacifica Graduate Institute, and teaches in the Depth Psychology Program with Specialization in Jungian and Archetypal Studies. She is author of several books on literary theory, gender and C.G. Jung including Jung as a Writer; Jung: A Feminist Revision; C.G. Jung in the Humanities; The Ecocritical Psyche: Literature, Evolutionary Complexity and Jung; and The Sleuth and the Goddess in Women’s Detective Fiction and Remembering Dionysus: Revisioning Psychology and Literature in C.G. Jung and James Hillman, as well as Jungian Arts-Based Research and the Nuclear Enchantment of New Mexico (July 2020).

Angela Borda is a writer for Pacifica Graduate Institute, as well as the editor of the Santa Barbara Literary Journal. Her work has been published in Food & Home, Peregrine, Hurricanes & Swan Songs, Delirium Corridor, Still Arts Quarterly, Danse Macabre, and is forthcoming in The Tertiary Lodger and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 5.